Disrupting Autodesk's Design Monopoly

A Conversation with Paul O'Carroll, Founder of Arcol

Autodesk: The Industry Goliath

For over 40 years, Autodesk has held a firm grip on the design software market. Anyone involved in the design and construction of infrastructure has extensively used their products. Let's acknowledge the reality: CAD and BIM have amplified the efficiency of architects and engineers by over 100x. From the days of pen and paper, the advent of computer-aided design revolutionized our ability to design, manage, and build infrastructure faster, better, and more efficiently. We all appreciate these advancements—so why not extend that appreciation to Autodesk?

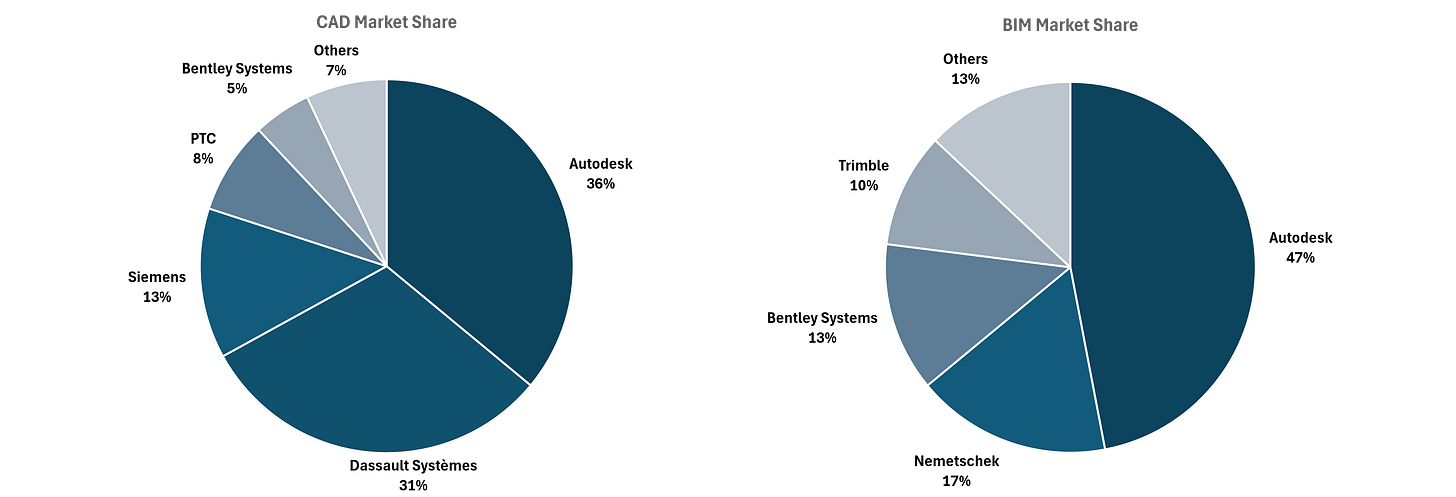

Over the years, however, Autodesk has tightened its hold on the industry, steadily maintaining a dominant market share. Several large players have attempted to compete but have never managed to dethrone the king of CAD. Many engineers and architects argue that Autodesk has become complacent in its cash-cow position, with little incentive to innovate. Owning roughly 36% and 47% market share in CAD and BIM, respectively (see graphic below), they've developed strategies to maintain their position that some consider restrictive. Critics suggest that while their barriers to competition are significant, the relentless progression of technology puts them at risk of disruption.

The beauty of the tech industry is that a handful of engineers in a garage can overturn a billion-dollar enterprise. Startups can fill the gaps where incumbents have grown complacent, scaling user adoption faster than it takes an incumbent to select a new office coffee blend. Startups embody the ultimate David versus Goliath narrative.

Today, we'll explore Autodesk's design monopoly and discuss Arcol, a startup daring to challenge the giant.

How did Autodesk Attain This Monopoly Position?

An engineer can't hear the word "CAD" without thinking of Autodesk. Much like how "searching online" immediately brings Google to mind for 90% of people, Autodesk's name is synonymous with computer-aided design. This is the advantage of being first to market. Not only were they pioneers in CAD, but they were also the first to market with BIM. In fact, the term BIM was popularized by Autodesk; they coined it and marketed it alongside their BIM solution, Revit.

Another reason for Autodesk's firm grip on the industry is the two-sided marketplace they've developed between engineers/architects and companies. The more architects who are proficient in Revit, the more companies adopt Revit, and vice versa. This network effect compels all parties to adopt the solution. How did they ensure architects are trained in Revit early-on? By providing free licenses to architectural schools, so that students graduate already fluent in Revit. As these new professionals enter the workforce, they naturally expect to use the software, prompting employers to embrace it—cementing Revit as the industry standard. Below is a graphic from NFX visualizing this two-sided marketplace.

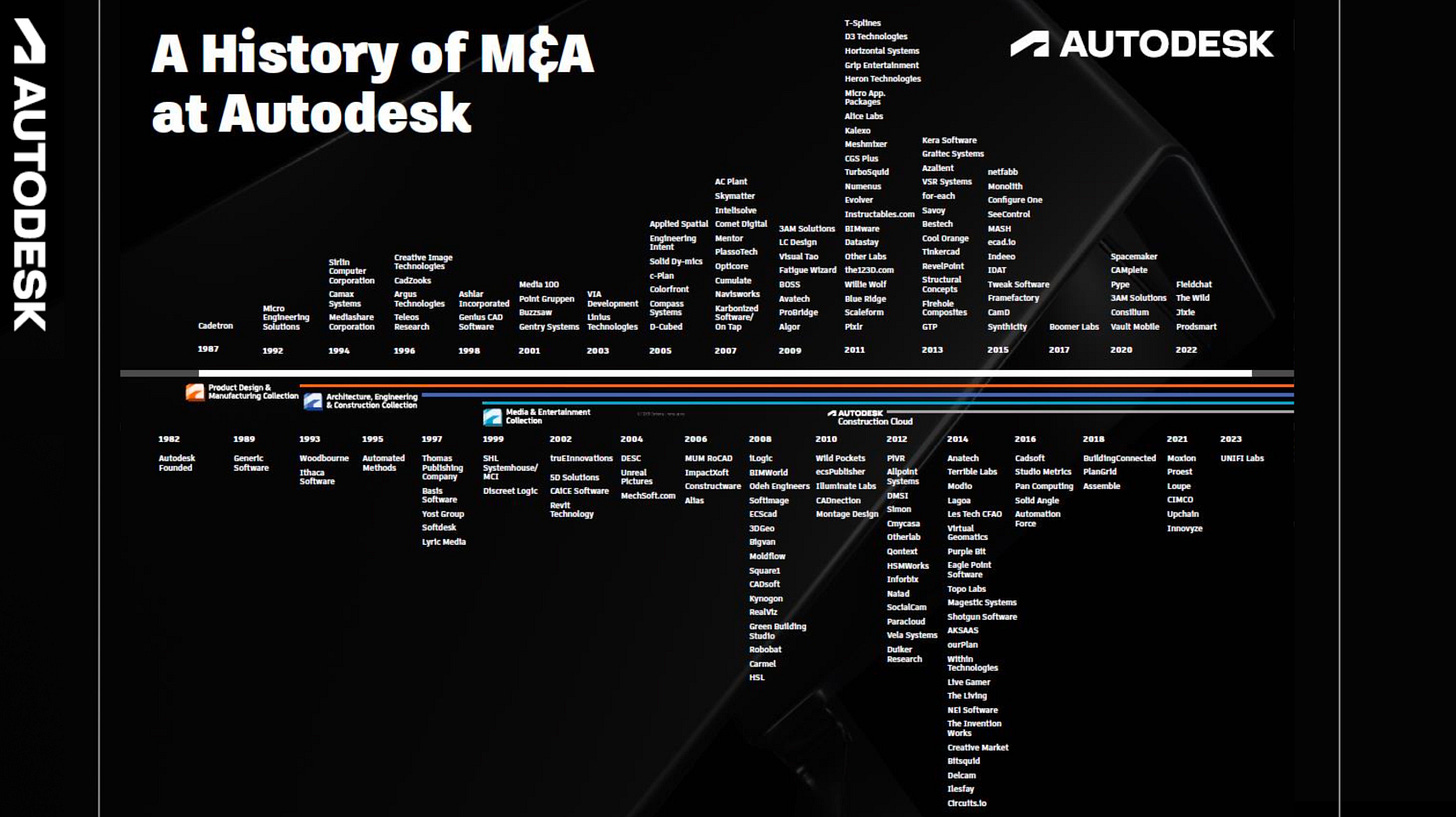

A significant factor in Autodesk's ability to maintain its monopoly is its massive cash flow. AutoCAD alone generates approximately $1.5 billion in revenue per year, with the entire AEC category totaling around $2.5 billion—Revit accounts for a substantial portion of this (source). This lucrative cash cow has allowed Autodesk to dominate the acquisition space. Any potential disruptor of AutoCAD or Revit has been swiftly acquired and integrated. They purchased Softdesk in 1997, Revit in 2002 (yes, Revit was an acquisition), Spacemaker AI in 2020, and over 80 others across 30 years. These acquisitions accelerated Autodesk's ability to vertically integrate into industry-specific domains and embrace new, cutting-edge technologies. Below is a history of Autodesk’s acquisitions since its founding by Revit.news.

Perhaps the most crucial factor bolstering Autodesk's position and working against startups is distribution. Autodesk boasts over 10 million users of AutoCAD alone, and it's estimated that around 60% of all architectural firms in the U.S. use Revit. If Autodesk wants to promote a new product, they can simply reach out to their massive customer base—or better yet, cross-sell within their existing products. They have instant access to hundreds of thousands of architecture and engineering firms at their fingertips.

Who Will Take Down the Giant?

To explore how Autodesk might be disrupted, I spoke with Paul O’Carroll, Founder and CEO of Arcol—a browser-based building design tool startup. Paul’s thesis is straightforward: incumbent design tools like Revit are inadequate, and "a lot of innovation in construction is held back by that design layer." So, how does O'Carroll plan to improve these archaic solutions? He believes a key issue is the lack of collaboration. His plan is to "move these tools natively to the browser, make them real-time collaborative, make them powerful, make them easy to use, and make them accessible." In other words, Arcol aims to be "the Figma for BIM." Notably, two of Arcol’s key investors are Dylan Field, co-founder of Figma, and Tooey Courtemanche, founder of Procore—a perfect collaboration.

O’Carroll’s thesis maintains a common theme: designers should not be held back by their design solution. He’s dedicated to making Arcol powerful and flexible. Designers should not need to adhere their work to the confines of a design solution. Arcol is built specifically to give as much creative expression as possible with an ambitious roadmap that doesn’t stray from this core belief. After all, why spend hours creating a building in Rhino only to rework it to meet Revit’s demands? With Arcol, designers retain full autonomy throughout the entire design process, free from unnecessary restraints.

Another value proposition of Arcol, is it serves as a single source of truth for all project data. In the traditional workflow, designers might use Miro for moodboards, SketchUp for modeling, Excel for pro-formas, and InDesign for presentations—juggling multiple tools and file formats. With Arcol, these tasks converge into one cohesive environment. No more messy software stacks that need constant updates; when you adjust the model in Arcol, associated costs, presentations, and other data fields update automatically. This minimizes context switching, allowing designers to spend more time designing rather than managing contrasting platforms. See the below GIF of Arcol’s multiplayer platform in action with all building data in one environment.

At first glance, this may seem like subtle improvements. However, when you consider the extent of collaboration needed in construction, its true value becomes apparent. Imagine a standard building design: how many stakeholders are involved? Architects, owners, general contractors, subcontractors, engineers—the list goes on. At each stage of the design process, these various groups view or comment on designs. In the "early concept and feasibility" stage, for instance, an architect can build out designs on Arcol in the browser. When it's time to share with the contractor and owner, they can simply send a link—no need for weeks of back-and-forth emails. As O'Carroll puts it, "that barrier to iterating on feedback... the friction is gone." By removing these needless iterations, designers can focus more on designing, and contractors can build faster. O'Carroll plans to tackle each stage of the design process one by one until Arcol serves as the single design platform where all stakeholders can collaborate.

After hearing O'Carroll’s thesis and solution, it's clear why AEC professionals would find this valuable. But is that enough justification to take on a behemoth like Autodesk? O'Carroll makes it clear that Autodesk’s lack of innovation and monopoly-like grasp on the design market have downstream impacts on the built environment. He states, "Whatever comes out in Revit 2026 really does impact the industry. Buildings will look different if there's some cool, new, innovative feature. Yet Autodesk doesn't push the industry forward." He essentially argues that the cities and buildings we inhabit daily are affected by the complacency of an incumbent—a sobering reality.

O’Carroll's key motivator to compete with Autodesk is simple: "the lack of innovation. The industry deserves better." It's not just frustrating that they fail to innovate; what's driving that lack of innovation is the financial incentive. He argues, "They know that Revit makes as much money as it physically can, so why would they bother to innovate on it, especially when no one's going to leave? They can't leave because there's no competitor." With a dominant market share, no startup competition, and systems in place to guarantee the stickiness of their product, AEC professionals are left with Revit as their only option—a massive industry with so much room for innovation, left in the hands of a giant unwilling to disrupt its guaranteed cash cow.

Not only is Autodesk Revit not innovative, but it also fails to innovate in one of the most critical workflows in the AEC process: the design layer. The design stage is arguably the most critical part of the building process. It acts as a map to guide the project and determines what the final solution will look like. By thwarting innovation at this crucial step, Autodesk negatively affects the entire industry. A delayed, overbudget, or poorly planned design layer will guarantee issues downstream in the engineering, construction, or even asset management phases (consider the Millennium Tower in San Francisco). O’Carroll states, "Everything in this industry is built upon that model. Yet the actual modeling layer has no innovation." This shows that Autodesk may be impacting not only designers but everyone in the AEC industry.

Arcol’s Collaborative Revolution

The reasons to compete with Autodesk are clear, but what's Arcol's adoption plan? Arcol's initial growth strategy is to tackle the design process piece by piece, starting with the "early concept" phase where most designers lack a solution specifically designed for winning projects. Since there is no standard tool at this early design stage—not even Revit—much of Arcol’s adoption has been organic and inbound.

So what's next? O’Carroll is betting big on collaboration across the entire design process. He mentions, "The core innovation that will be the reason we win or we don't win is our focus on collaboration, and that'll be the biggest change that we bring to the market." While there are other significant product benefits—such as generative AI, smart design tools, improved usability, and seamless implementation—the essence of Arcol's offering is collaboration.

Autodesk lacks the capability to implement a truly collaborative platform effectively. As a company with over 14,000 employees, it moves slowly, and such large organizations often struggle with bureaucracy. Not only do they move slowly, but the task of creating a collaborative platform is extremely challenging. O’Carroll notes, "It's incredibly hard to do properly, and I don't see anybody seriously investing in it." The complexity of this undertaking is evident, as some of Arcol's first hires were early engineers from Figma. Collaboration is not an easy task, especially in an industry as complex as AEC.

Another massive value proposition of Arcol over Revit is the new opportunities that collaboration brings to various stakeholders. With the design process existing on one shared browser platform, it opens the door for stakeholders to share their input throughout the process. As O’Carroll says, there will be a "blurring of the lines of when stakeholders get involved." Previously, architects owned the model for the entire design process, with contractors having minimal visibility. Now, contractors can provide input to architects during the process, potentially improving the construction phase. While the architect retains the final say, involving contractors earlier can lead to a more efficient construction process, benefiting the owner.

Contractors dislike being locked out of the design process because it prevents them from contributing to a feasible model. O’Carroll quoted a large contractor partner: "As soon as a model goes into Revit, we're at the behest of the architect." The value of collaboration democratizes design. Instead of constantly requesting changes from the architect, stakeholders can comment directly within the browser.

Some might argue that architects will resist this, fearing it could diminish their creative freedom. However, it will likely enable architects to produce more creative designs, as they can receive contractor sign-off promptly. Consider Figma as an example: when Figma was released, product designers weren't upset that product and engineering managers could see and provide input on their designs. They appreciated the ability to share a single link, allowing stakeholders to view and contribute throughout the process. Ultimately, seamless collaboration leads to greater efficiency. As O’Carroll puts it, "Everybody should be singing from the same hymn sheet and should have an actual single source of truth."

O’Carroll's vision is straightforward: customers recognize the value propositions that collaboration brings; Autodesk is too big and slow to implement this effectively; Arcol extends collaboration across the entire design process; and eventually, there will be no need for Revit. As O’Carroll predicts, "Autodesk will become the IBM of the computing age."

The Future of Design

What does the future of architectural design look like? O’Carroll envisions that two to three decades from now, the well-defined business models within AEC could look entirely different. Barriers between areas of expertise will continue to diminish, allowing various stakeholders to bring more processes in-house or even absorb entire segments of work. As O’Carroll puts it, "As tools get more collaborative, we will likely see a change in the contractual nature." We may witness a world where general contractors absorb some design work, architects take on engineering tasks, and owners oversee contractors more closely. In the early 2000s, we saw the emergence of design-build contracts; one day, we might see the entire AEC chain integrated into a single contract. This would represent "an actual disruption of the architectural business model," as O’Carroll describes. He acknowledges that this is speculative and, if it occurs, would likely take many decades.

The future of AEC is elusive amid rapid technological changes, but what's in store for Autodesk? Incumbents, especially in AEC, are notorious for innovating through acquisitions. Collectively, Autodesk, Trimble, and Procore have acquired over 150 companies over the past decade. I asked O’Carroll, "Can Autodesk just buy their way out of complacency?" He responded with a firm "No." The reason is that they are both blessed and cursed with Revit. It's a cash cow that dominates the market, but to build a new platform like Arcol, they would need to completely deprecate Revit—which they can't do. O’Carroll notes, "They can never dismantle Revit as quickly as a startup could." As the market leader, they are almost cursed to stay loyal to the product that got them there; any deviation from the core product could be seen as uncertainty and risk customer churn.

O’Carroll does note that other incumbents are better positioned for the "next big design platform." Companies like Procore or Trimble could potentially purchase an architectural design startup and build a platform from the ground up. O’Carroll seems enthusiastic about this idea, stating, "This is the decade for the incumbents to step up—to either build innovative solutions or invest heavily in someone who is." Regardless of whether an incumbent buys their way forward or a startup builds the future, the industry is poised for positive change.

Challenging an established industry leader is no easy task, but O’Carroll appears ready for the battle. His passion for improving the AEC space is evident. This led me to ask, "What advice do you have for other founders seeking to disrupt industry leaders?" He put it simply: "Focus on building a beautiful product; everything else follows. Hire an incredible team, build a beautiful product—that's the advice. Nobody's building beautiful products, specifically in AEC." Amid countless initiatives, KPIs, stakeholder demands, and investor expectations, what truly distinguishes great companies is an unwavering focus on building an exceptional product. In an industry already resistant to technology, AEC demands exceptional products. If we want to see the digitization of AEC, we need entrepreneurs who prioritize "building a beautiful product" as their number one priority.

You think Revit is holding back AEC? look at Civil 3D. Our needs are much less and performance of "models" or 2.5D entities is slow and evolutionary tech built on 1980s CAD. We created Builterra.com to do the same thing you are looking to do here...one source of Geospatial truth without Esri, all loaded into an Azure database. We came at it from the Construction Management and Inspection angle and just now are coming back to Mapping and ultimately Web based design components connected to the construction objects. It's the technical convergence where this is the best solution for AEC. With open or common data standards, you could access our cloud (owner side bids and design) database, render it as you need to and collaborate easily.

Autodesk's monopoly needs a good old-fashioned busting, but it's definitely not going to happen by letting contractors into the design process LMAO